عمومی

علایق: http://www.iranian.com/main/member/majid-naficy http://www.iranian.com/mnaficy

عضو از ۱۳ آذر ۱۳۹۱

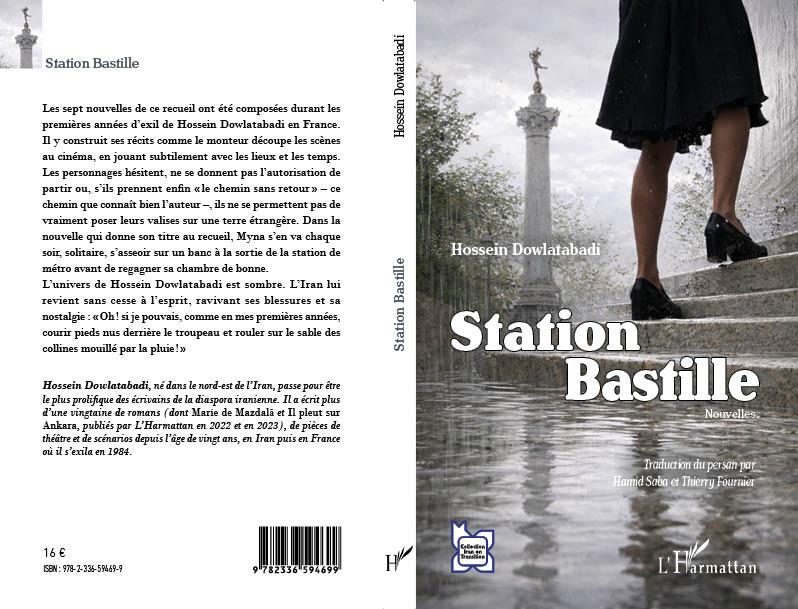

کتاب حسین دولتآبادی: ایستگاه باستیل

«ايستگاه باستيل» مجموعۀ چند داستان کوتاه است که از سال ۱۳۵۷ تا سال ۱۳۷۳ در ايران و خارج از کشور نوشته شده اند. این کتاب نخستین بار به کوشش زنده یاد داریوش کارگر، نوینسندۀ تبعیدی و مدیر انتشارات افسانه در اوپسالا ( سوئد) چاپ و منتشر شد، چاپ دوم آن به وسیلۀ هادی خوجینیان، مدیر نشرمهری در لندن انجام گرفت و امسال به همت عطا آیتی، انتشارات آرماتان – در پاریس، ترجمۀ فرانسوی آن را چاپ کرد.

.

Les sept nouvelles de ce recueil ont été composées durant les premières années d’exil de Hossein Dowlatabadi en France. Il y construit ses récits comme le monteur découpe les scènes au cinéma, en jouant subtilement avec les lieux et les temps. Les personnages hésitent, ne se donnent pas l’autorisation de partir ou, s’ils prennent enfin « le chemin sans retour » – ce chemin que connaît bien l’auteur –, ils ne se permettent pas de vraiment poser leur valise sur une terre étrangère. Dans la nouvelle qui donne son titre au recueil, Myna s’en va chaque soir, solitaire, s’asseoir sur un banc à la sortie de la station de métro avant de regagner sa chambre de bonne. L’univers de Hossein Dowlatabadi est sombre. L’Iran lui revient sans cesse à l’esprit, ravivant ses blessures et sa nostalgie : « Oh ! si je pouvais, comme en mes premières années, courir pieds nus derrière le troupeau et rouler sur le sable des collines mouillé par la pluie ! »

Hossein Dowlatabadi, né dans le nord-est de l’Iran, passe pour être le plus prolifique des écrivains de la diaspora iranienne. Il a écrit plus d’une vingtaine de romans (dont Marie de Mazdalā et Il pleut sur Ankara, publiés par L’Harmattan en 2022 et en 2023), de pièces de théâtre et de scénarios depuis l’âge de vingt ans, en Iran puis en France où il s’exila en 1984.

.

.Edition L'Harmattan

7 Rue de l'École Polytechnique . 5 .........· 01 40 46 79 20

دسته: تعیین نشده

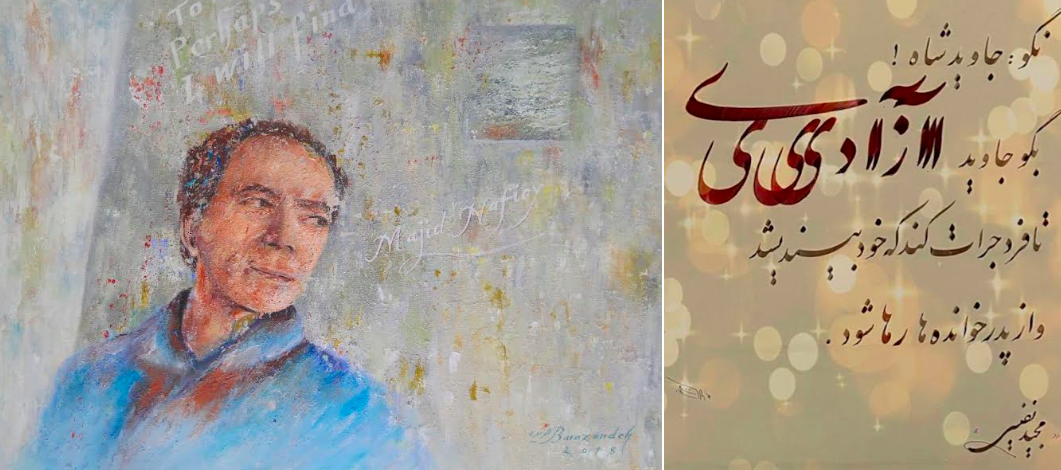

مجید نفیسی: نقاشی و خوشنگاری

دسته: تعیین نشده

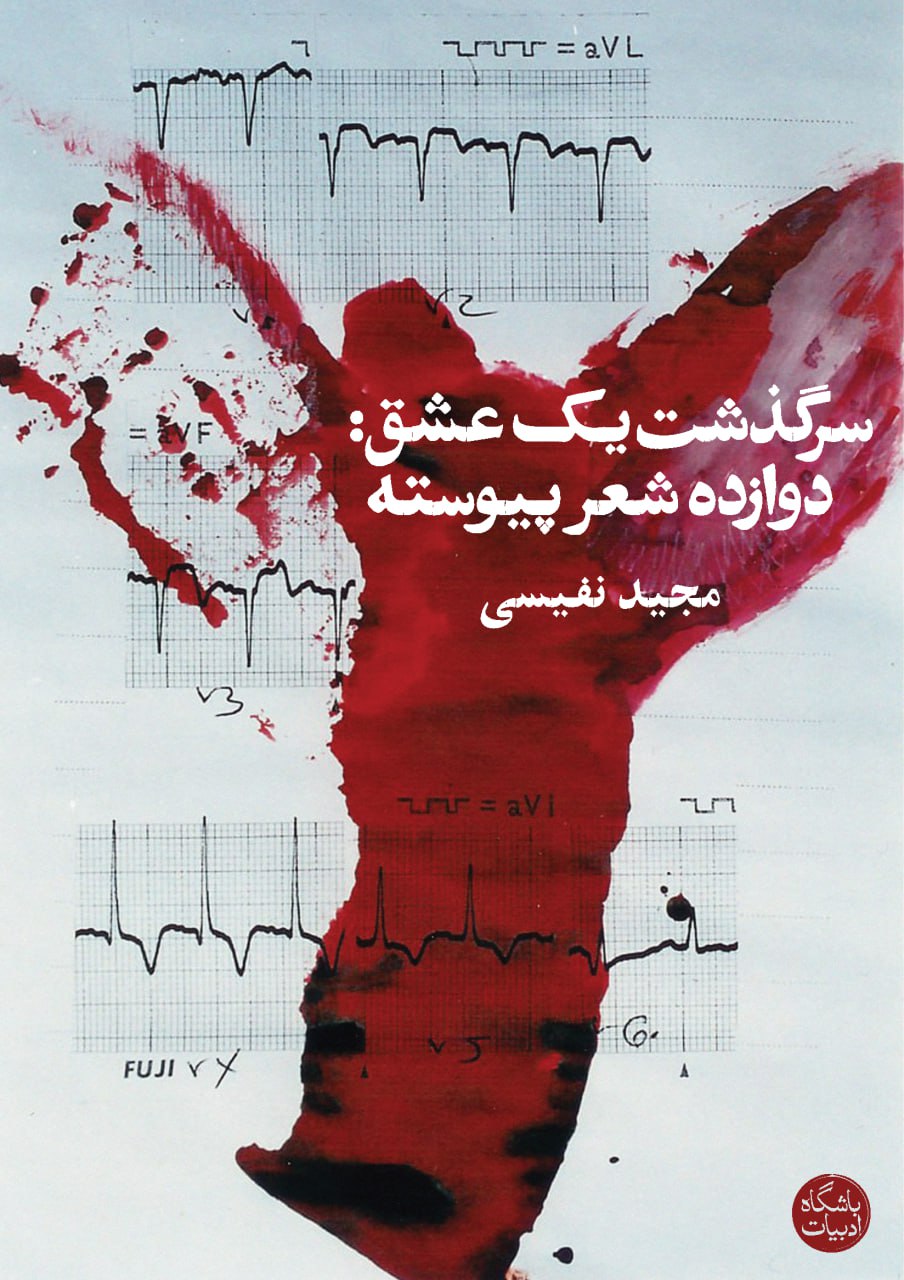

دسترسی رایگان به کتاب تازهی مجید نفیسی

سیمین بهبهانی در نامهای از تهران مورخ اول آوت 1999 به مجید نفیسی نوشت:

"آقای مجید نفیسی عزیزم، "سرگذشت یک عشق" مجموعهی دوازده شعر زیبای شما را آقای گلشیری عزیزم به من داد. هدیه محبی از آن سوی دنیای جداییها. خوشحالم که دور از یار و دیار، شاخه ي برومندی با استقلال و تفرد و به دور از همانندیها میبالد و بارور میشود. نمیدانم این چند سطر به شما خواهد رسید یا نه. به هر حال من باید بنویسم که شعری ماندگار دارید بی آن که از معیارهای نشاندار زمان پیروی کرده باشید یا به عمد به دنبال غرابتهای نوجویانه رفته باشید. پیش از این شعر "نفرین" شما را در "چشم انداز" خوانده بودم و به دنبال نشان گوینده میگشتم. تبریک مرا بپذیرید."

دسته: تعیین نشده

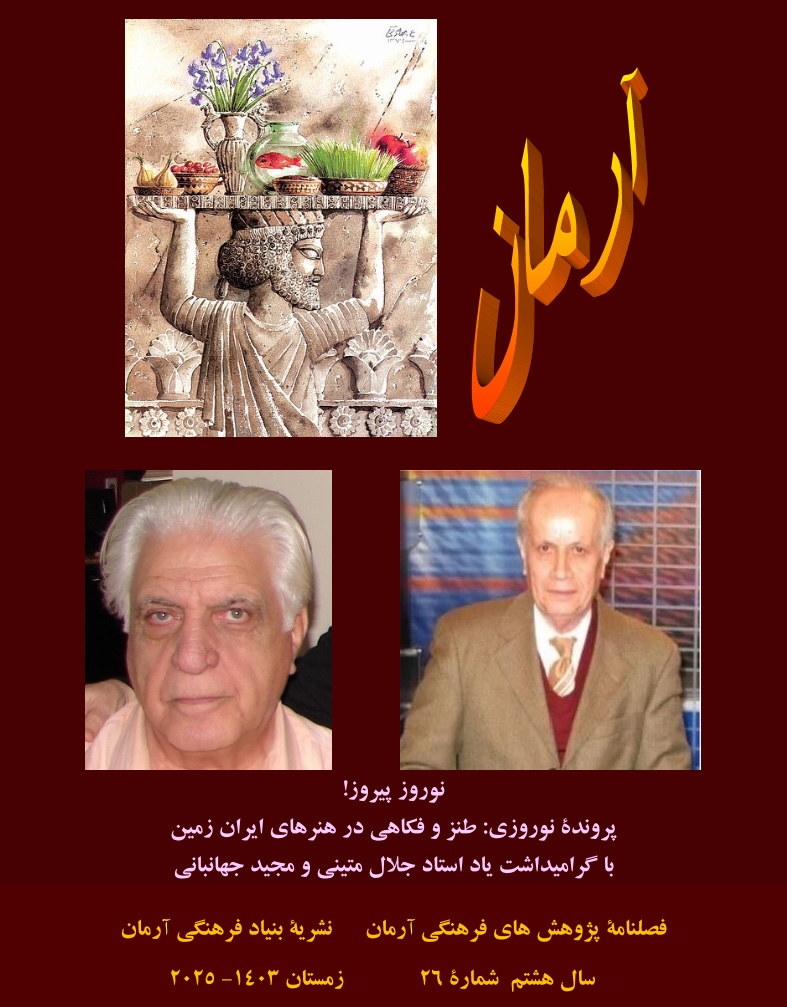

فصلنامۀ پژوهش های فرهنگی آرمان شماره ۲۶ منتشر شد

پروندۀ نوروزی: طنز و فکاهی در هنرهای ایران زمین

متن کامل آرمان ۲۶ در لینک زیر:

https://armanfoundation.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Arman_Magazine_26b.pdf

بنیادگذار: ساموئل دیان

سردبیر فصلنامه و تارنما: شیریندخت دقیقیان

image.png

فهرست آرمان ۲۶

ساموئل دیان: نوروز پیروز!

پروندۀ نوروزی: طنز و فکاهی در هنرهای ایران زمین

الف.ت.صالح: مانیفستِ طنز در اندوه فراگیر: تأملی بر دو روی سکّۀ اندوه و طنز

حسن جوادی: طنز دهخدا در نظــم و نثر در مقایسه با طنز پردازی صابر و جلیل ممد قلیزاده در نشریۀ ملانصرالدین

مجید نفیسی: توفیق و من

شیدا محمدی: درآمدی بر طنز در ادبیات ایران زمین

علی سجادی: دامنۀ اعتراض از بحر طویل تا رَپ جدید!

عباس یوسفیانی: اجرای خلاق طبیب اجباری اثر مولیر در ایران

پژوهش ها و آفرینش های ادبی، هنری و فرهنگی

ناصر کنعانی: نگاهی به زندگانی پُرماجرای خسرو پرویز ساسانی، شاهنشاه ایران و انیران ؛ دنباله ای بر دو داستان "خسرو و شیرین" و "شیرین و فرهاد"

توفیق حیدرزاده: اخترشناسی و کیهانشناسی در میانرودان (بین النهرین) و ایران – به مناسبت نوروز

ارژنگ اسعد: معرفی کتاب سپهدار – فتحاللهخان اکبر به قلم گلی اکبر کاشانی

معرفی مجموعه ادبیات زنان آفریقا، تحقیق و ترجمه فریده شبانفر

یادبودها

یادنامه ای برای استاد جلال متینی:

علی سجادی: زندگی پر بار یک خدمتگزار همیشگی فرهنگ ایران: دکتر جلال متینی و سالشمار زندگی و آثار او

یادنامه ای برای مجید جهانبانی:

شیریندخت دقیقیان: وقتی خداحافظی کرد و رفت...

مرتضی حسینی دهکردی: یادی از مجید میرزا جهانبانی در دانشکدۀ کشاورزی کرج

محمد حسین ابن یوسف: دوست نازنین

تاریخ

مجید جهانبانی: مادربزرگ، خانم شوکت السّلطنه قهرمان

فلسفه و عرفان

اسفندیار طبری: نظری به کتاب فناجویی یا انسان خدایی؟ پژوهشی در عرفان ایرانی و حکمت قبالا

تازه ها و جاودانه های شعر به گزینش علیرضا اکبری

بهارانه ها: شفَیعی کدکنی؛ هوشنگ ابتهاج؛ قیصر امین پور؛ سهراب سپهری؛ سیمین بهبهانی؛ حسین منزوی

پیشاپیش از شما برای به اشتراک گذاشتن لینک آرمان ۲۶ در شبکه های اجتماعی سپاسگزاریم.

دسته: تعیین نشده

کتاب هماندیشی چپ ـ ویژهی انقلاب ۵۷

از انقلاب۵۷ نزدیک به نیم قرن گذشت؛ از انقلابی، یا قیامی، که امید بود آزادی بیاورد و نیاورد. و امید بود رفاه و عدالت بیاورد و نیاورد.

نزدیک به نیم قرن از انقلابی، یا قیامی، گذشت که به وعدهی سفرهای نان و سقفی بر سر، از دستهای خالی پل ساخت و بر شانههای خسته سوار شد و گرسنه را به حراج کلیه واداشت و گود نشین را به گورخوابی.

اینگونه بود که فضای ذهنی همهی این نیم قرن تا امروز اشباع شد از بیشمار پرسش:

چرا انقلاب شد؟ و چرا و چگونه به سرنوشتیِ چنین دچار شد؟ راز شکستی چنین سنگین در چه بود؟

آیا انقلاب ۵۷ گریزناپذیر بود؟

چگونه بود که در ماههای مشرف به بهمن ۵۷، در سراسر سپهر سیاسی کشور، گروه و گرایشی یافت نمیشد که در خیزش عمومی حضوری نداشته باشد و نقشی نپذیرفته باشد؟

و چرا منهای بخشی از دهقانان، طبقهی اجتماعی دیگری نبود که در آن ماهها به قطار انقلاب سوار نشده باشد؟

در کندوکاو تاریخ، بهعنوان مسئول تیرهروزی و فلاکت کنونی، انگشت اتهام را میتوان به سمت کدام جریان سیاسی یا اجتماعی گرفت؟

جایگاه و نقش چپ در انقلاب و شکست آن کجاست؟

امروز، سوژهی رهاییبخش چطور تعریف میشود؟ و راه نجات از کدام سمت؟

زمینههای رشد راست افراطی وشبهفاشیست به چه اندازه است؟

این گرایشها تحت کدام شرایط ممکن است موفق شوند تودهی اتمیزه و بیشکل را به خدمت «ناجی» و «پیشوا»ی دیگری در آورند؟

از بهمن ۵۷ هر چه بیشتر دور شدیم و غبار فراموشی بر حافظهها بیشتر نشست، بار ذهنی پاسخهایی که به چنین پرسشهایی داده شده سنگین تر شد و راه بر جعل و فریب و وارونهسازی هموارتر. و نیز هر چه تودهی محروم و فرودست خستهتر، خشمگینتر و مایوستر شده، و خود رهانی را دشوارتر یافته، قلب واقعیتها آسانتر شده و هزینهاش کمتر. در چنین بزنگاهی است که بازماندههای فرقهی #پهلوی فضای روانی موجود را مناسب یافتهاند و به سودای بازگشت به قدرت و تحمیل دور باطلی دیگر به تاریخ، از تاریکخانههای لاس وگاس بیرون امدهاند. به کنار از مساعدت فضای ذهنی، این فرقه برای ریلگذاری افکار عمومی به داشتن پشتوانههای مادی بسیاری دلگرم است. میکوشد ازمنابع مالی هنگفت و هژمونی رسانهای تا اطاقهای فکر و حمایت شماری از دولتها و برخی دستگاههای اطلاعاتی همه را به خدمت انحراف ذهنیت افکار عمومی و انقیاد آن در آورد.

رو در رو با چنین تهدیدهایی، پاسخدادن به پرسشهایی که فضای عمومی را اشباع کرده ضرورتی است حیاتی؛ بهویژه از سوی کسانی که همچنان بر حقانیت قیام مردم علیه حکومت پهلوی باور دارند. #هماندیشیـچپ در عمل به این تکلیف میکوشد گامی بردارد و انتشار ویژهنامهای که پیش رو دارید بخشی از این کوشش است. مجموعهای که گرد آمده؛ مقالهها، یادداشتها، گفتوگوها و اسناد، حاصل یاری و مشارکت بسیاری از نویسندگان، هنرمندان، کنشگران سیاسی و اجتماعی، پژوهشگران و تحلیلگران داخل و خارج کشور است که به دعوت ما پاسخ مثبت دادهاند. ضمن قدردانی از یکایک انان، لازم است تأکید شود آنچه تا کنون انجام شده، تنها مقدمهای است بر آنچه بسیار گستردهتر و فراگیرتر باید دنبال شود. با این امید که در گامهای بعد از یاری و هماندیشی طیف هر چه وسیعتری از افراد و گرایشهای #چپ برخوردار گردیم.

دسته: تعیین نشده

بیانیه: اسائۀ ادب به آرامگاه زنده یاد غلامحسین ساعدی و اعتراض ما

هتک حرمت آرامگاه غلامحسین ساعدی توسط فردی که ادعا میکند جامعهشناس و از هواداران رضا پهلویست نه تنها یک عمل شنیع و غیرقابل توجیه است، بلکه نمادی از بحران عمیق فرهنگی و سیاسی جامعه ماست.

این عمل صرفاً یک توهین شخصی نیست، بلکه اقدامی سیاسی با هدف سرکوب اندیشه و انتقامجویی از منتقدان است. انتخاب غلامحسین ساعدی به عنوان هدف، به دلیل دیدگاههای مترقی و انتقادی او و همچنین نقش برجستهاش در ادبیات و روشنفکری ایران، کاملاً هدفمند بوده است.

بیانیه حاضر با امضای دهها نویسنده و شاعر و مترجم و روزنامهنگار و استاد دانشگاه و کنشگر سیاسی و مدنی به شدت به حادثه هتک حرمت به آرامگاه غلامحسین ساعدی در گورستان پرلاشز واکنش نشان داده است. امضاکنندگان با زبانی تند و انتقادی، این عمل را محکوم کرده و آن را نشانهای از رذالت، شقاوت و فاشیسم دانستهاند.

این بار رذالت و شناعت در گورستان پرلاشز، درتبعید رخ داد.

سالها است که جیره خواران و مزدوران حکومت ننگ و نفرت و جنایت اسلامی عزیزان مردم ما را گور به گور میکنند، سنگ قبر شاعران و آزادیخواهان میهن ما را میشکنند و در تبعید، فاشیستهائی که با وعدههای دولت اسرائیل، این نماد جنایت علیه بشریت، متوهم شدهاند، وقاحت را به جائی رساندهاند که آرامگاه نویسندۀ محبوب و مردمی ایران را در پرلاشز با پیشاب آلوده میکنند. زهی دنائت، شقاوت و رذالت! بیشک موجودی که بر مزار نویسندهای با نفرت و کینه ورزی مثانهاش را خالی میکند که عمری علیه دیکتاتوری و فاشیسم مبارزه کرده، شکنجهها شده، زندانی کشیده، در ایران و در تبعید رنجها برده و آثار ارزشمندی به ادبیات ایران ارزانی داشته است، موجودی که پرچم اسرائیل را به دوش میکشد و در گورستان پرلاشز پاریس آن را بر مزار غلامحسین ساعدی به اهتزاز در میآورد و برای نابودی نسل اندیشمند، با فرهنگ، هنرمند و مبارز ایران شعار میدهد، بی شک لمپنی فاشیست و بیفرهنگ و منحط است، هرچند اینهمه فقط ظاهر امر است و به شخص او محدود و منحصر نمیشود، بلکه طرز تفکر و رفتار و کردار بازماندگان حکومت منقرض ستمشاهی و طالبان و آرزومندان بازگشت سلطنت است که هر بار در گوشهای از دنیا و به شکلی بروز و تجلی پیدا میکند. این رفتار و گفتار تفاوت ماهوی با شقاوت و شناعتی ندارد که جمهوری اسلامی به مدت چهل و چند سال در حق انسانهای مبارز و مترقی و دگراندیشان روا داشته است و روا می دارد؛ هردو آبشخور معین و مشترک و سیاست یگانهای دارند: نفرت و انزجار از اندیشمندان، روشنفکران، هنرمندان مترفی و قلع و قمع آنها…ما که همواره ارزشهای انسانی و حرمت کرامت انسانها را پاس داشتهایم و پاس میداریم، هتک حرمت به آرامگاه نویسنده مردمی ایران را محکوم میکنیم و ضمن اعتراض و ابراز تنفر و انزجار به این رفتار شرمآور و ضد انسانی و شعارهای فاشیستی، توجه مردم آزادیخواه و مبارز ایران را به رشد فاشیسم و خطری جلب میکنیم که در این دوران پرآشوب، پس از فروپاشی حکومت اسلامی، آیندۀ مردم و مملکت ما را تهدید میکند.

دسته: تعیین نشده

دریغی بر پایان کار "آوای تبعید"

مجید نفیسی

با شمارهی چهلویک "آوای تبعید" در سه جلد, کار این مجلهی پربار پس از هفت سال از بهار 2017 تا پائیز 2024 به پایان میرسد و من که چند ماهی است از این موضوع دردآور آگاهم و نتوانستهام ویراستار آن اسد سیف را از این خواست منصرف کنم, دریغ میخورم زیرا این مجله نه تنها بستری پربار برای ادبیات فارسی در تبعید فراهم کرد بلکه بخاطر روش بردبارانهی ویراستارش دربرگیرندهی همهی نویسندگان در تبعید بود که غالبا به دلیل اختلافات شخصی و سیاسی نمیتوانند یکدیگر را تحمل کنند بیآنکه این فراگیری, به کیفیت کار مجله آسیبی رساند. یکی از جلوههای این منش دربرگیرندگی اسد سیف را میتوان در شمار دهها سردبیران مهمان دید که با آزادی کامل ویرایش شمارهای از "آوای تبعید" را به عهده گرفتند یا شمارههایی که به عرضهی ادبیات قومی ایران چون ادبیات ترکمنی, عربی و ترکی و همچنین ادبیات زنان و همجنسگرایان ایرانی اختصاص یافته است.

اسد سیف با انتشار چهلویک شمارهی "آوای تبعید" به همهی ما نشان داد که میتوان با حسن نیت و گشادهنظری, بر جو تنگبینی و فرقهگرایی در میان اهل قلم ایرانی پایان داد و آزادی سخن را با بردباری نسبت به دگراندیشان همراه کرد. امیدوارم که اسد سیف کار دربرگیرندهی خود را در اشکال دیگر با همان پیگیری پیشین ادامه دهد.

سی اکتبر دوهزاروبیستوچهار

****

چهلویکمین شماره آوای تبعید که در واقع آخرین شماره آن است در حجمی نزدیک به هزار صفحه در سه جلد منتشر شد. این شماره به "درگذشتگان به تبعید" اختصاص دارد و به یاد نویسندگان، شاعران، مترجمها و پژوهشگرانی فراهم آمده که در خارج از کشور درگذشتهاند.

این سه جلد فراتر از "زندکینامه"ها و "آنتولوژی"های معمول، خواسته است نوری بتاباند بر بخشی از هستی اجتماعی و فرهنگی این افراد. در حد توان خواسته است سیمای آنان را در ارزش آثارشان و میراث فرهنگی آنان، بازیابد و حداقل اینکه فراتر از یک زندگینامه باشد.

چنین مجموعهای تا کنون و در این حجم منتشر نشده است. و این به این معناست که باید امیدوار شد تا این کارِ هنوز ناکامل "آوای تبعید" را کسانی دیگر کاملتر کنند.

در این مجموعه از نزدیک به چهارصد شخصیتی یاد شده که هر یک به شکلی از کشور خویش تارانده شدهاند و در جغرافیای خارج از ایران عمر به پایان رساندهاند.

دانلود جلدهای این شماره از "آوای تبعید":

جلد نخست:

https://tinyurl.com/2ya6emn8

جلد دوم:

https://tinyurl.com/29aos4oh

جلد سوم:

https://tinyurl.com/2btr4adm

دسته: تعیین نشده

کتاب تازهی مجید نفیسی: شاهدی برای عزت

شاهدی برای عزت

مجید نفیسی

"شاهدی برای عزت" مجموعهی سی شعر از مجید نفیسی است به یاد همسرش عزت طبائیان که در 17 دی 1360 در زندان اوین تیرباران و در گورستان خاوران دفن شد. شاعر آمریکایی نیومی شهابنای در بارهی شعر "شاهدی برای عزت" مینویسد: " یکی از پرقدرترین شعرهای جهان, آکنده از عشق و حقیقت و اندوه. مجید تو شاعر بزرگی هستی. این بر من روشن شده از همان باری که اولین شعرت را شنیدم. تو براستی شاهدی بزرک هستی."

اینک نخستین شعر کتاب "گنج نشاندار":

"هشت قدم مانده به در

شانزده قدم رو به دیوار

کدام گنجنامه از این رنج خبر خواهد داد؟

ای خاک!

کاش میتوانستم نبض تو را بگیرم

یا از جسم تو کوزهای بسازم.

افسوس!

طبیب نیستم

کوزهگر نیستم

تنها وارثی بینصیبم

دربهدرِ گنجی نشاندار.

ای دستی که مرا چال خواهی کرد!

نشانِ خاک من این است:

هشت قدم مانده به در

شانزده قدم رو به دیوار

در گورستانِکفرآباد."

برای خرید این کتاب میتوانید به سایت نشر آفتاب یا فروشگاه آنلاین شرکت لولو مراجعه و نسخه کاغذی کتاب را به قیمت هشت (8) دلار آمریکا خریداری کنید.

دوستانی که مایل به خرید نسخه الکترونیکی کتاب هستند، میتوانند مبلغ 5 دلار آمریکا به حساب پی پال نشر آفتاب با آدرس

aftab.publication@gmail.com واریز کنند، فیش پرداختی را برای ما بفرستند تا نسخه الکترونیکی کتاب برایشان ارسال شود.

عزیزانی که ساکن ایران هستند و مایل به خواندن نسخه الکترونیکی این رمان هستند، کافی است به نشر آفتاب ایمیل بفرستند تا برای پرداخت 20 هزار تومان هزینه کتاب، در ایران راهنمایی شوند.

آدرس سایت نشر آفتاب

www.aftab.pub

آدرس پست الکترونیکی نشر آفتاب

info@aftab.pub

aftab.publication@gmail.com

شناسنامه کتاب

نام کتاب: شاهدی برای عزت

نویسنده: مجید نفیسی

ژانر: مجموعه شعر

سال انتشار: 1403 خورشیدی

نقاشی روی جلد: نوشین نفیسی

اجرای طرح جلد: نادیا ویشنوسکا

صفحهپرداز: مهتاب محمدی

ناشر: نشر آفتاب، نروژ

شماره شابک: 2-7907-4457-1-978

دسته: تعیین نشده

نشر آفتاب منتشر کرده است: "مادر و پدر" مجید نفیسی

"مادر و پدر" مجموعهی سیوشش شعر از مجید نفیسی است در دو بخش "مادرِ مادران" و "پدرِ پدران" با شعرهایی چون "نشانیهای مادرم", "در بازار ادویهی اصفهان", "شمشیر در حوضخانه" و "دیدار خمینی" که شخصی را با عمومی, وطن را با تبعید و گذشته را با حال و آینده درهممیآمیزد. شاعر سرشناس آمریکایی نیومی شهابنای در باره این شعرها مینویسد: "این شعرها باشکوهند و مرا عمیقا تحت تاثیر قرار دادند. تو استاد شعر پرروح هستی."

برای تهیه این کتاب به فارسی میتوانید به سایت نشر آفتاب یا فروشگاه آنلاین شرکت لولو مراجعه و نسخه کاغذی کتاب را به قیمت ده (10) دلار آمریکا خریداری کنید.

دوستانی که مایل به خرید نسخه الکترونیکی کتاب هستند، میتوانند مبلغ 6 دلار آمریکا به حساب پی پال نشر آفتاب با آدرس aftab.publication@gmail.com واریز کنند، فیش پرداختی را برای ما بفرستند تا نسخه الکترونیکی کتاب برایشان ارسال شود.

عزیزانی که ساکن ایران هستند و مایل به خواندن نسخه الکترونیکی این مجموعه داستان هستند، کافی است به نشر آفتاب ایمیل بفرستند تا برای پرداخت 15 هزار تومان هزینه کتاب، در ایران راهنمایی شوند.

آدرس سایت نشر آفتاب

www.aftab.pub

برای خرید نسخه انگلیسی از آمازون اینجا کلیک کنید.

دسته: تعیین نشده