Hassan Rouhani and Hassan Khomeini attend a ceremony with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in Tehran

Dr. Ali Mamouri

Amwaj

The race to succeed Iran's 86-year-old supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is no longer a hypothetical parlor game; it has become a tense, critical and increasingly public power struggle at the heart of the political establishment. As Tehran navigates a crippling economic decline, a series of painful regional setbacks and deep domestic discontent, the political elite is actively maneuvering for the post-Khamenei era. Two names, in particular, now stand out as the most formidable contenders for the apex of power: moderate former president Hassan Rouhani and Hassan Khomeini, the politically astute grandson of the Islamic Republic's founder.

The contest is multi-layered, extending deep into the religious, political and security establishments that form the very foundation of the state. With the Office of the Supreme Leader commanding significant influence over the political stage, the stakes are immense. The battle for succession is a fight to determine Iran's ideological and strategic direction for the next generation.

The crisis and the apex of power

The twilight years of Iran's first supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1900-1989), offer insights into how current confrontations may unfold.

Although Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri had been formally designated as Khomeini's successor, a coalition led by Khamenei, then-parliament speaker Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Khomeini's son, Ahmad, ultimately engineered his removal. Through a sophisticated campaign of lobbying inside the Assembly of Experts—an elected clerical body tasked with selecting the next supreme leader—and mobilizing influential networks, Montazeri was pushed aside and replaced by Khamenei. That process remains one of the most complex power transitions in the history of the Islamic Republic.

The current competition appears sharper and more intense. As the Office of the Supreme Leader has become deeply institutionalized under Khamenei's 36-year reign—commanding major sway over political, economic and security affairs—rivalries now extend beyond clerical elites to include factions within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), political parties, key technocratic institutions and even transnational Shiite networks.

This intense infighting is fueled by growing domestic discontent. Public confidence in the state has plummeted due to economic stagnation, endemic corruption and a perceived strategic retreat in the region. Critics are increasingly assigning the state's failures directly to Khamenei's policies, both domestically and abroad. What is particularly notable is that this criticism is no longer confined to the opposition; it is now emerging from within the political establishment itself, including former high-ranking officials.

The veteran challenger's gambit

Among the most prominent internal critics of the status quo in Iran are former presidents Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-13), a conservative, and moderate Hassan Rouhani (2013-21). Despite their vast ideological differences, both men have openly questioned Khamenei's leadership and decision making, effectively accusing him of steering the country into crisis. While Ahmadinejad, not being a cleric, is formally unsuitable for the role of supreme leader, Rouhani remains a serious—if controversial—figure at the center of discussions over succession.

Rouhani's recent and unusually sharp criticisms of the conservative-dominated establishment—particularly his sniping at Khamenei's approach—are not simply a matter of political dissent; they are widely viewed as a calculated effort to position himself for the succession. Hardline factions have pushed back aggressively, declaring that the moderate politician “will never achieve his dream,” underscoring the raw intensity of the internal rivalry.

Yet, Rouhani remains a formidable contender. Few figures in the Islamic Republic have accumulated his level of experience and expertise: he has served as first deputy speaker of the parliament, was the founding secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, held multiple terms in the Assembly of Experts, and completed two presidential terms. These unparalleled roles have granted him access to all major power centers—political, military and intelligence—necessary to navigate a succession crisis.

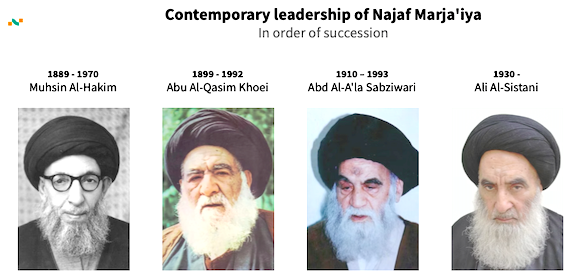

Crucially, Rouhani retains a strong level of credibility within the Shiiite seminaries of both Qom and Najaf. His warm reception by Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani during a 2019 visit to Iraq—a visit that stood in stark contrast to Sistani's refusal to meet Ahmadinejad—was a powerful signal of his standing among the transnational clerical networks. While these networks cannot decide the succession, they quietly shape the broader atmosphere of political legitimacy in Iran, an atmosphere that is essential for any potential supreme leader.

The grandson's unique appeal

Hassan Khomeini, the grandson of Khamenei's predecessor, has likewise emerged as a strong contender, combining a unique blend of credentials. Unlike other symbolic heirs, he successfully combines religious authority, political positioning and institutional connections in a way that could allow him to unify competing factions during a delicate transition.

Khomeini's ties to the powerful Guard Corps are significant. His consistent public defense of the Islamic Revolution and his call for stronger deterrence capabilities—including his blunt remark that “deterrence depends on power, not on smiles”—have resonated deeply within the security establishment, which wields immense political influence.

Khomeini's outspoken support for the Iran-led ‘Axis of Resistance', alongside his criticism of Israel, the United States and even Turkey's cooperation with Israel in Syria, further aligns him with the strategic worldview of Iran's security elites. At the same time, he possesses a moderate stance on domestic affairs. His support for greater social freedoms and diplomatic engagement gives him crucial cross-factional appeal and offers a potential path to restoring public legitimacy without fundamentally undermining the state's core revolutionary principles.

Importantly, Khomeini's religious standing is impeccable. With decades of serious seminary study, he was trained under some of Shiite Islam's most respected jurists and has taught Dars-e Kharej—the most advanced seminary level—earning him credibility across the clerical communities. This position is further reinforced by his family network: through both lineage and marriage, he is connected to prominent Shiite families, including the Sadrs and Bahr Al-Ulums. His brother's presence in Najaf and marriage to Grand Ayatollah Sistani's granddaughter further strengthens essential ties with Najaf's influential clerical establishment.

These factors have contributed to a favourable view of Khomeini among senior scholars in Iraq, several of whom—concerned about Iran's declining regional influence and its implications for Shiite communities in the region—told Amwaj.media that they regard him as one of the few candidates capable of stabilizing Iran's direction and restoring its regional standing.

The dynasty question

The intensity of the current race is highlighted by the improbability of a long-rumored candidacy: a speculated gambit by Mojtaba Khamenei, son of the current supreme leader.

The 56-year-old cleric undeniably wields considerable behind-the-scenes influence within Iran's power structure. In this context, figures such as Faezeh Hashemi—an outspoken daughter of late president Rafsanjani—have even suggested that he could become “Iran's MBS,” referring to Saudi Arabia's modernizing crown prince. Yet, the younger Khamenei's path to the top position appears highly improbable for two fundamental reasons.

First, Shiite religious tradition features a strong resistance to hereditary succession. Throughout the history of clerical leadership in Shiite Islam, it has been exceedingly rare for the son of a marja—the highest rank of scholar—to directly inherit his father's position. This powerful norm explains why both Mojtaba Khamenei and Mohammad Reza Al-Sistani—despite their religious standing—are not viewed as plausible successors to their fathers. Only after an intervening leader serves and passes does the door sometimes open for the son of a previous marja to rise, thus avoiding the appearance of dynastic transfer. Within this traditional framework, Khomeini—and not a son of Khamenei—fits far more naturally into the established succession logic.

Second, and more crucially, the Islamic Republic was founded in explicit rejection of hereditary monarchy. Having the incumbent supreme leader's son directly inherit the position would fundamentally undermine the ideological foundations of the Islamic Revolution and severely damage the political system's legitimacy, both internally and within the broader Shiite world. Any perception of dynastic succession would be politically explosive and could provoke resistance from key clerical, political and military factions.

Looking ahead

Conservative former president Ebrahim may be late, but his absence from current discussions over leadership succession is in some ways still revealing.

Until Raisi's demise in a helicopter crash in northwestern Iran last year, the former chief justice was widely viewed as the conservative establishment's preferred candidate—carefully positioned through his presidency and earlier roles to consolidate backing from clerical, judicial and security circles. His death removed what had been the most clearly manufactured succession pathway for hardliners. Since then, no comparably prominent or consensus figure has emerged from within the conservative camp. This vacuum helps explain why succession debates have shifted away from hardline ideologues towards figures with broader institutional reach and cross-factional appeal. Against this backdrop, the supreme leader has wished to involve the IRGC in the process of pre-selection of candidates to gain the support of the Guard Corps for his successor, informed sources in Tehran told Amwaj.media.

All in all, the rivalry over Khamenei's succession is not a future event; it is already underway, multi-layered and more intense than in the sole previous transition to replace a supreme leader. As political, clerical and security networks recalibrate for a post-Khamenei landscape, figures like Khomeini and Rouhani represent two critical, competing strands in a far broader—and increasingly consequential—power struggle that is already reshaping Iran. How these dynamics may be impacted by sudden and unpredictable events, including the possibility of Khamenei being targeted by adversaries of the Islamic Republic, remains to be seen.

Dr. Ali Mamouri is a Research Fellow at Deakin University. He previously served as strategic communication advisor to the Iraqi prime minister (2020-22). He is also the former editor of the Iraq Pulse at Al-Monitor (2016-23), and a former lecturer at the University of Sydney and the University of Tehran. His work has been published in leading media outlets, including Al-Monitor, The Conversation, Washington Institute, BBC Persian, and Al-Jazeera.

Comments