Mehrdad Aref-Adib

Violence has defined the Islamic Republic from its beginning.

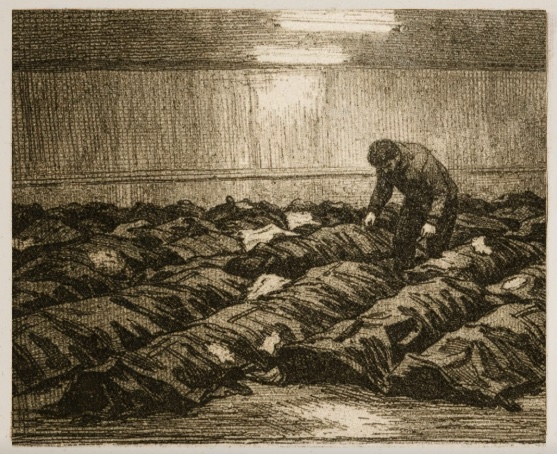

Examine the record since 1979 and the pattern is unmistakable. Violence has not been an accident. It has been foundational. The images emerging from Iran now, bodies laid in rows, gunfire into crowds, public executions, are shocking not only because of their brutality, but because of their display. This time, the violence is not merely deployed. It is exhibited. It is harsher, more explicit, less concealed.

What once relied on silence and blackout now appears almost demonstrative. The message is no longer implied. It is shown.

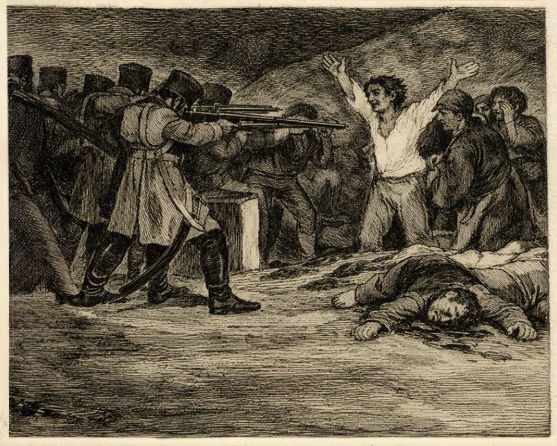

When Francisco Goya created The Disasters of War, he stripped war of heroism. There are no victories in those prints, only bodies, firing squads, hunger and grief. Goya did not portray chaos. He portrayed design. Violence in his work is deliberate, structured and methodical.

The early years of the Islamic regime followed the same logic. Summary executions and revolutionary courts with minimal due process secured power quickly. Fear proved efficient. Bodies became warnings.

Through the 1980s, opposition groups were crushed, prisons filled and torture became widespread. In 1988, thousands of political prisoners were executed after secret hearings. This was not loss of control. It was organised elimination. It was governance through example.

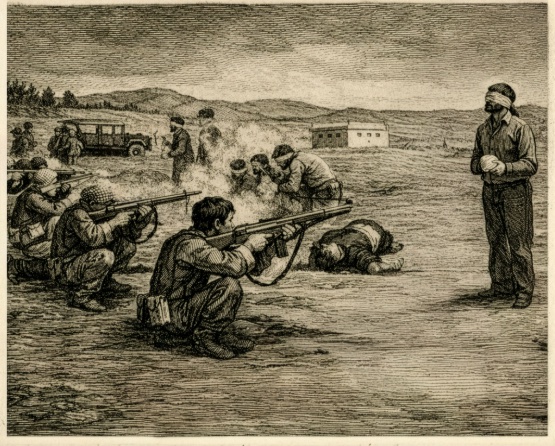

In 1999, student protests were met with raids and beatings. In 2009, millions took to the streets. Security forces responded with live ammunition and mass arrests. The killing of Neda Agha-Soltan became a global image, not because it was unique, but because it was visible. Violence is not only physical. It is communicative. It tells the population what is permitted and what is not.

In 2019, fuel protests spread across the country. The internet was shut down as security forces fired on demonstrators, killing hundreds. When communication is cut, violence becomes harder to document and easier to expand. Silence becomes part of the architecture.

In 2022, the death of Mahsa Amini triggered nationwide protests. Women cut their hair in public. Funerals became demonstrations. Executions resumed. The images were stark: blood on asphalt, families waiting outside detention centres, faces marked by shock and grief. They felt painfully close to Goya’s world.

Now, in 2026, reports suggest thousands have been killed in the latest crackdown. Drones monitor gatherings. Weapons are deployed swiftly. Executions are carried out just as quickly. Across decades, the same tools reappear: fear, execution, mass arrests, public spectacle, and control of information.

Since 1979, the Islamic Republic has used violence not only in moments of crisis but as a method of rule. That is not exaggeration.

The photographs emerging from Iran today are not artworks but evidence. Yet they evoke a disturbingly similar feeling. History leaves images behind, and over time those images accumulate into a record that cannot be erased.

Comments